Reframing Resilience - ESEA Heritage Month 2025

ESEA Heritage Month takes place in September in the UK. The theme for 2025 was on ‘Reframing Resilience’.

I had planned to do a little blog series on this and some considerations for mental health workers, but my health had other plans and no writing was done! I didn’t want to see the month go without sharing some thoughts.

‘ESEA’ stands for East and South East Asian, a collective term often used in the UK to describe people with heritage from across locations in East Asia and South East Asia. This includes China, Hong Kong, Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and others. It acknowledges both the diversity and the shared experiences of these communities.

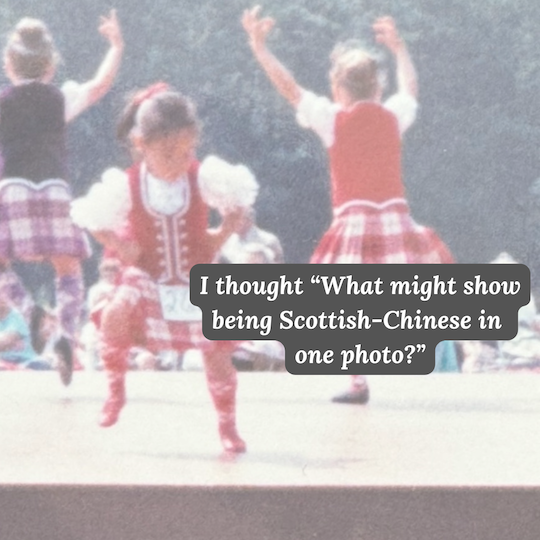

I was born in Scotland to a biological family from Hong Kong but raised by a white Scottish family. It was usual (at least in my area at that time) that children would be looked after; much of the Chinese community worked long and unsociable hours when they moved to the UK in restaurants and takeaways. I think this context and my background have greatly helped my acceptance of differences, and my approach to providing therapy. I’ve also personally experienced being ‘in-between’ cultures and working through this complexity from a young age.

Often, I’ve found in therapy that people think that resilience means coping with everything life throws at them all by themselves. Resilience is often defined as the ability to adapt and recover from adversity but also requires supportive relationships to develop this and sometimes this is the biggest challenge people can face: seeking help from others. Within ESEA communities, this can be intensified by the ‘model minority’ or ‘silent and enduring’ stereotype. It derives from the idea that people of ESEA ethnicity are submissive, hard-working, high-achievers, and have an elevated societal status free from oppression. This can make it difficult to speak with others about any challenges and not connect with support that could be helpful.

Right now, it can feel difficult being in a minority group. During and since the pandemic, it was documented that there was a surge in racism and discrimination towards the ESEA community. The origin of the outbreak in China led to the virus harmfully being referred to as the ‘Chinese virus’ and is said to be a factor in the rise of racial hate crimes and discrimination towards the ESEA community. In the media, even when stories did not involve the ESEA community, the irrelevant use of images containing ESEA members perpetuated the ‘Chinese virus’ slurs. Within the UK, there is more awareness and publicising of the hate crimes and discrimination faced by minority groups in addition to more exposure to anti-immigrant views (a collation of reports and data can be found from Sesame Organisation).

This is part of the social context that the individual experience is contained. Experiencing racism, discrimination and hate aren’t just painful in the moment, they can leave people feeling unsafe, isolated, or unwelcome in their own communities, which has lasting impacts on wellbeing. Experiencing racism and hate can increase feelings of shame, anxiety, or hypervigilance, and can lead to self-silencing or withdrawing from support. It may also fracture someone’s sense of belonging, especially for those navigating multiple cultural identities.

There is an increasing emphasis on openness about mental health and accepting that it’s ‘Okay not to be okay’ through various mental health campaigns in Scotland. This contrasts with the idea of keeping things private within families, and there may be internal conflict, or a push-pull, experienced by Scottish ESEA individuals when navigating living within both cultures. On the one hand, mental health campaigns and peers may encourage openness and vulnerability. On the other, cultural values may emphasise privacy, stoicism, and prioritising family reputation. This can develop thoughts such as ‘I don’t talk about how I really feel’ and ‘it’s weak to need support’. Living between these worlds can bring unique challenges.

People don’t need to choose between their ESEA heritage and their Scottish identity. For those of us in the ESEA community, resilience can mean reconnecting with heritage, finding belonging in shared experiences, and giving ourselves permission to seek help without shame. It also means recognising the toll of racism and discrimination while holding on to pride and solidarity. Importantly, building understanding and kindness towards yourself as you navigate these is beneficial. Having a ‘village’ can be useful, but it may feel non-existent to begin with. You might start by finding an online or in-person group or activities of shared interest from ESEA members or focused on ESEA networking.

If you’re looking to start therapy, then finding a therapist who is culturally competent and aware, and open to exploring your unique experiences is essential. Sometimes, clients have shared that they were encouraged to cut off contact from their families in therapy, because of conflict or cultural clashes, which can dismiss deeply held cultural values. For many, family is central even when it brings challenges. Therapy can create space for both self-care and meaningful family ties, rather than forcing a choice. (I note here that if there is risk of harm or reported abuse, appropriate risk and safeguarding measures will be taken within therapy.)

If you’re reading this and you’re not part of the ESEA community, you can still play a role. Consider how you can challenge discrimination and racism and support ESEA-led community initiatives. Essentially, reach in and listen when people share their experiences and check in with your friends. These acts of solidarity can make a big difference.